The history of the Women’s Hospital provides an overarching look at women’s and maternal health in Winnipeg, but the true nature of care can best be understood in the actions of the people. Programs, research, and initiatives undertaken at Health Sciences Centre Winnipeg (HSC), often pioneered by doctors, nurses, and staff, remain the foundation of care and insight into women’s and maternal health.

Some programs pioneered at HSC – like research on Rh disease – have been adopted around the globe. Others – like Kangaroo Care – have been conceived elsewhere and embraced here. These are staff-led initiatives that come from the hearts and minds of individuals and teams at HSC concerned about the delivery of care to patients and their families. Staff have acknowledged and, in some cases, overcome women’s health needs in life and death situations. The Women’s Hospital is a resource and location for the total care of women, including labour and delivery, antepartum patient care, postpartum care, gynecology, neonatal care, ambulatory care, high risk care, gynecological oncology, surgery, and end of life care.

Though not exhaustive, contained in this history is a synopsis of programs developed at Women’s Hospital over the past 100 years that have been vital to the development of women’s and maternal health in Winnipeg and – sometimes – around the globe.

Prenatal Clinic, 1919 & Postnatal Clinic, 1926

In January 1919 a weekly Prenatal Clinic was added to the Outpatient Department at HSC for the “care of expectant mothers”, providing much-needed support in the community. This clinic was established for expectant mothers who would not otherwise have the opportunity for medical attention and advice. Attendance at the Prenatal Clinic was steady with over 125 patients visiting during its first year. The Prenatal Clinic worked closely with the Winnipeg General Hospital Social Services Department after the birth of the baby; many of the patients were unmarried mothers who were offered follow-up support that included at least one home visit. The success of the Prenatal Clinic grew and it eventually was offered twice a week.

By the mid-1920s, services expanded with the opening of a weekly Postnatal Clinic. This clinic, organized in 1926, aimed to provide mothers with advice on care for their babies and themselves. Follow-up visits were essential for the success of these programs. The involvement of the Winnipeg Hospital Aid and Convalescent Board was also very important as they donated layettes – clothing, linens, and sometimes toiletries for a newborn child – to the Social Service Department who provided emergency necessities for a baby when leaving the hospital.

The Prenatal and Postnatal Clinics were very well attended throughout the late 1920s and into the 1930s. In 1931, there were over 4,000 visits to the Prenatal Clinic. Many families were being supplied with layettes due to the Depression and the economic hardships they were facing. Unmarried mothers were also increasing in numbers, which placed greater demand on the Social Service Department. The depressed economy and decrease in revenue forced the trustees to close the Outpatient Department in 1933 – which included the Prenatal and Postnatal Clinics.

In 1953, the Prenatal and Postnatal Outpatient Clinics were resurrected and were once again well-received and attended. As of 2019, the Prenatal and Postpartum Nursing Clinics help to coordinate complicated pregnancies and deliveries to provide the best birthing experience possible before and after birth. They also offer an Adolescent Prenatal and Postpartum Clinic – or Teen Clinic – open to youth living anywhere in the city.

Winnipeg Rh Laboratory, 1944

The Winnipeg Rh Laboratory was established in 1944 by Dr. Bruce Chown for research in Rh blood antibodies. Though originally located in the basement of the Children’s Hospital, the Rh Lab was moved to the Women’s Pavilion in 1956.

Rhesus factor negative syndrome, or Rh disease, is a potentially deadly condition affecting in-utero and newborn babies. People are born either Rh positive or negative. When a mother and her unborn child have different Rh factors – if, for example, one is positive and one negative – the mother’s immune system might attack the baby. Potentially, this could lead to complications in the development of the heart, lungs, and brain. In some cases, it could lead to death in-utero, or life-threatening complications after birth. Chown – assisted by Marion Lewis, Laboratory Technician – contributed to the elimination of this threat by showing that the immune system was sensitized by the fetus bleeding into the mother.

The Rh Lab gained worldwide recognition when a baby with Rh disease was saved with an exchange transfusion. Success continued with the discovery that amniotic fluid analysis that gave a 95% accurate prediction of Rh disease. In 1964, the first intrauterine fetal transfusion in North America took place by Dr. John Bowman and Dr. Rhinehart Friesen.

Chown worked with Dr. John Bowman and others to develop and test a serum called Rh Immune globulin, which was licensed in Canada in 1968 and used to prevent Rh disease. The vaccine was commercialized and marketed as WinRho SDF (The “Win” stands for Winnipeg). The drug was sold in 35 countries by the Manitoba-based research firm Cangene. Cangene was sold to Emergent BioSolutions, where WinRho remains in production. Chown was the first from the province to complete landmark research that led to the commercialization of a major new drug – work that ultimately laid the foundation for all research in the province to follow. Rh testing is now part of all perinatal testing services, and can be screened at blood services locations around the world.

At present, Rh clinic patients report to the first floor of Women’s Hospital. A dedicated area will be available in the new facility, to continue the ground-breaking and life-saving work of Dr. Bruce Chown and Marion Lewis.

For more information, see the University of Manitoba’s digital exhibit featuring the Winnipeg Rh Laboratory.

Newborn Service, 1947 & Premature Nursery, 1950

The Newborn Service Department was formed in 1947, under the direction of pediatric staff and in collaboration with obstetrics, to support premature and full term babies requiring special care. The Premature Nursery was opened in 1950 in the Maternity Pavilion, and became the predecessor for neonatal intensive care units. In 1956, when the Children’s Hospital moved to its William Avenue location, critically ill babies were transferred from the Maternity Pavilion to the Intensive Care Nursery, and healthy, premature, or babies needing special care remained at the Pavilion.

In the early 1970s, under the direction of Dr. Henrique Rigatto, a lab was built in the Women’s Centre (Pavilion) beside the Premature Nursery specifically to investigate the control of respiratory system during the neonatal period. Dr. Rigatto was the lead in this research study that considered problems such as the relationship between period breathing, apneaic spells, and sudden infant death (SID) during the early months of life. It was hoped that by doing research into the control of the respiratory system during the neonatal period, apneaic spells – where premature infants would stop breathing – could be prevented. In 1996, Rigatto received a research grant to study pacemaker cells – believed to generate and sustain breathing – in the brains of newborns.

For more information, see our History of Neonatal Intensive Care.

Gynecologic Oncology, 1956

Although women diagnosed with cancer had been treated at Winnipeg General Hospital for over 50 years, in 1953, a consultative committee made up of gynecologists, radiotherapists, and pathologists worked together to focus on patient care/treatment for women with pelvic carcinoma. In 1956, the fifth floor of Women’s Pavilion was converted from a student residence to semi-private wards for gynecological patients. A year later, a Gynecological Operating Room was established on the fourth floor and the name of the Maternity Pavilion was changed to the Women’s Pavilion to reflect the expanding functions and services in the area of women’s health. By 1959, the capacity for gynecological services in the Women’s Pavilion nearly doubled with the opening of Ward S5 (Wing). In 1970, a framework was established for the training and placement of subspecialties in Gynecologic Oncology.

Dr. Garry Krepart established the first Fellowship for Gynecologic Oncology in Canada in 1981 at the University of Manitoba’s campus at HSC. For many years it remained one of only two programs available in the country. Fellows from this program have populated Canadian medical schools and hospitals as deans and department heads. These graduates are shaping gynecologic oncology education and practice across Canada and internationally. The program provides exposure to all aspects of care for women with gynecological malignancies of the reproductive tract and offers trainees exposure in both the clinic and operating room.

Donna Romaniuk managed the Gynecology Oncology program in the 1990s, providing more progressive care. Donna Britton became the first Clinical Nurse Specialist in Gyne-Oncology during this time.

Gynecology and Gyne-oncology care and procedures have grown significantly over the years. The current Women’s Hospital has room for approximately 33 patients, and more for those requiring palliative care. Services will expand when the new HSC Women’s Hospital opens.

Family Planning Program, 1965

The Family Planning Program started in 1965 in Manitoba and was run out of the Outpatient Department at the Women’s Hospital. The program was initiated by Dr. T.M. Roulston, head of Obstetrics and Gynecology Department. Roulston was a strong advocate of family planning throughout his career. The Family Planning Clinic was run on a weekly basis and provided support related to birth control and infertility.

One of the services provided by the Clinic was voluntary sterilization. Approval was based on several criteria including a woman’s age and number of children and the signed agreement from her husband and doctor. Sterilizations had to be approved by a Committee composed of a gynecologist, psychiatrist, and surgeon. Sometimes the Committee would propose more conventional methods such as the pill and diaphragms over surgical intervention. Prior to this, sterilization was only granted in cases of severe physical or psychiatric health concerns. In an interview with the Winnipeg Free Press for 30 January 1970, Roulston noted the dramatic increase of sterilization operations due to the fact that “people have become more concerned with family planning.” In the 1970s, Roulston was joined by Dr. Richard Boroditsky.

Today, Planning Service and Pregnancy Counseling at Women’s Hospital have become more nurse-managed, and patients are educated about alternative choices and decisions. Nurses assess patients and remain with them, providing contiguous care to increase the comfort of patients in a vulnerable time. They also encourage care alternatives, such as music therapy. The Roulston Procedure Room, in which the pregnancy termination program operates, is only one of two available in Winnipeg. In 2018, medical – rather than surgical – pregnancy terminations became available.

Clinical Investigation Unit and Colposcopy Clinic, 1969

In 1969, both the Clinical Investigation Unit (CIU) and Colposcopy Clinic opened. The Colposcopy Clinic was seen as having particular value for patients presenting with abnormal cytology in pregnancy.

The Clinical Investigation Unit operated out of Winnipeg General and in the basement of the Maternity Pavilion where research projects focused on coagulation problems in gynecological and obstetrical practice, bladder function, and the treatment of Rh disease by intrauterine transfusion. The CIU worked closely with the Rh Lab in the programme for prevention of Rh sensitization by passive immunization. Dr. Helen Toews joined the Department in a full-time capacity in 1969. She was a former resident who conducted her post graduate work at Johns Hopkins Hospital and had a special interest in colposcopy, Pediatric Gynecology, and bladder physiology.

The Colposcopy Clinic is still an Outpatient program at Women’s Hospital wherein care providers continue to diagnose and treat abnormal cell changes.

Neonatal Intensive Care Unit, 1972

A designated Intensive Care Nursery (ICN) was opened in the Women’s Centre in 1972. The ICN started with ten beds and the capability of ventilating newborns, and expanded over the next decade. A new Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) opened at HSC Children’s Hospital in 1986, and the Nursery in Women’s Hospital became an Intermediate Care Nursery (IMCN).

For more information, see our History of Neonatal Intensive Care and our History of the Intensive Care at HSC, which includes a brief look at the Neonatal unit.

Fetal Biophysical Profile Score (BPS), 1979

Dr. Frank Manning developed the Biophysical Profile Score (BPS) along with colleagues at the University of Southern California in 1979. It is used worldwide as an indicator of fetal health. The BPS can assess the health of a high-risk fetus by monitoring breathing, gross body movement, tone and heart rate reactivity, and amniotic fluid volume.

“Prior to the BPS test, fetal assessment was limited to the fetal heart rate because it was the only variable that could be measured accurately with the technology in use at the time. With the introduction of high-resolution ultrasound in the mid-1970s, it became possible to monitor a number of variables that in combination gave a much more accurate assessment of the health of a high-risk fetus.”

(Dr. Frank Manning, 1996 – NOVUM – Research at the University of Manitoba).

When Dr. Manning returned to the University of Manitoba in 1981, he and his research team studied the relation between the last BPS result and the condition of a high-risk fetus before delivery. The result of this research provided conclusive evidence that incidence of fetal death was significantly lower in high risk pregnancies where BPS scoring was used in management.

In 1994, Dr. Manning and his team determined the BPS score to be an excellent diagnostic tool to predict, and in some cases prevent, cerebral palsy. A low BPS score may indicate fetal distress, high acid content in the blood (antepartum academia), and low oxygen content in the blood (hypoxemia) – both academia and hypoxemia are known causes of cerebral palsy. Early intervention in terms of delivery of a fetus in the 28th week could save lives or prevent the baby from becoming sicker in the womb.

Keepsake Program, 1980s

The Keepsake Program was created for parents who experience pregnancy loss at the Intensive Care Nursery (later named the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit). In the early 1980s, NICU nurses provided photographs and sometimes inked footprints to parents whose baby had died. A group of nurses and the unit’s social worker began to augment these cherished gifts in the early 1990s by asking women’s church groups to sew small flannel gowns. The first church group to provide gowns was from the Sargent Avenue Mennonite Church. One NICU nurse in particular, Michelle Nowakowski-Beel, personally sewed hundreds of cloth envelopes that were provided to families to hold their keepsakes.

In the mid-1990s, NICU began to create molded hand and footprints to replace the inked prints. This started when a couple – who were both blind – lost their baby and the nurses wanted to provide something tactile to suit their needs. Sam, a technician from pathology, came up with an idea to use wax for a mold and then plaster to recreate the baby’s face, hands, and feet. Soon after, Clinical Resource Nurse Debra Armitage found a source for dental molds and she created a process that is still in use today. Hand and foot molds are created for all babies who pass away. They are placed into a plaster frame that the nurses decorate with beads and other items to spell out the baby’s name and create a work of art for the parent’s to remember their baby. Many nurses have contributed to these keepsakes over the years. All materials were paid for from funds donated to HSC Children’s Hospital by families and friends and other members of the community.

The Keepsake Program was also implemented in the Women’s Hospital on a similar timeline with the assistance of the White Cross Guild and social workers. A small room is available where parents can pay their respects and say their goodbyes. The Program will see a substantial improvement at the new HSC Women’s Hospital. A dedicated, respectful, and sensitive space will be available that includes a sitting area for family.

Fetal Assessment Unit, 1980

The Fetal Assessment Unit (FAU) is the primary program for prenatal diagnostic services for the population of Manitoba, Northwestern Ontario, and parts of Nunavut. In 1980, the FAU was pioneered in Winnipeg by Dr. Frank Manning for potentially high-risk pregnancies among women in Winnipeg.

Multidisciplinary patient care is provided in the FAU with Prenatal Genetics, Neonatology, Pediatric Surgery, Pediatric Cardiology, Pediatric subspecialists, and Social Work involvement. All advanced invasive procedures such as cordocentesis, fetal transfusion, shunt placement, and amnioreduction are performed at this unit. Advanced fetal echocardiography services are provided by a Pediatric Cardiologist at the Variety Children’s Heart Centre at HSC. Fetal MRI is provided by two Pediatric Radiologists at HSC. Nuchal translucency measurement in the first trimester is performed for eligible patients primarily in the FAU at Women’s Hospital.

Today the Fetal Assessment Unit provides consultative assessment, treatment, and teaching services for patients who have shown indications of problems that may be encountered by either the mother or baby during the prenatal period or during pregnancy. The FAU offers non-stress testing, biophysical profile scoring (BPS), genetic amniocentesis, and fetus and nuchal testing. The treatments and procedures are often managed by nurses and supported by fetal specialist physicians, resulting in a more holistic and supportive care.

Neonatal Transport Unit, 1981

When the Women’s Hospital was built, the building was separate from the Winnipeg General Hospital to reduce the spread of infectious diseases to women and children. A tunnel connected the hospitals a few years later to improve efficiency and accessibility for women’s health. The Children’s Hospital, Thorlakson Building, and Women’s Hospital are similarly connected by tunnel. However, it became apparent that children requiring Neonatal Intensive Care (NICU) required a safe mode of transportation between the delivery and patient rooms and the NICUs. A transport unit was created in 1981 to transport children from one building to the next quickly and safely. In 1998, staff developed the ground transport incubator system. The transport incubator has gone through a series of upgrades over the years, but is still essential for keeping newborn babies safe on their travels. The incubator is also used in the Neonatal Transport Program, assisting in the transport of newborn babies from around the province.

For more information, see our History of Neonatal Intensive Care.

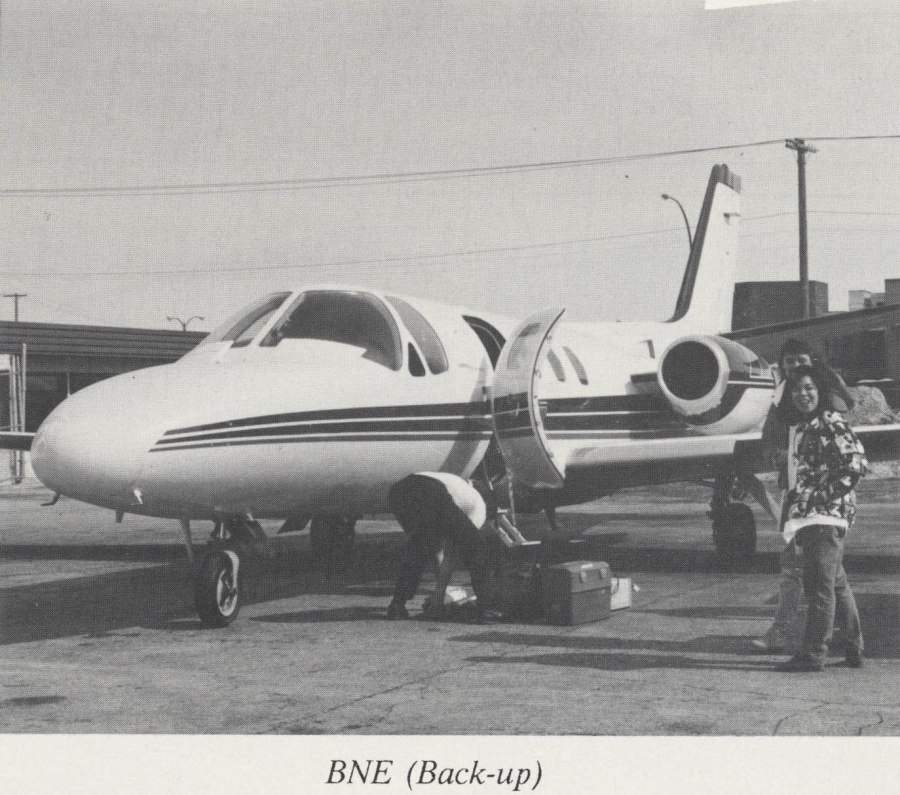

Neonatal Transport Program, 1981

The Neonatal Transport Program was founded in 1981 by Dr. Henrique Rigatto, Director of NICU at HSC. The Neonatal Transport program in Winnipeg provides care and transport for critically ill infants throughout Manitoba, Northwestern Ontario, and Nunavut to HSC or St. Boniface General Hospital. In 1981, the transport unit served an 80 mile radius around Winnipeg, which was extended to 100 miles in 1989. In 1986 a group of physicians, nurses, and respiratory therapists volunteered to be air-lifted to children in need from Manitoba, Northwestern Ontario, and Nunavut.

In 2019, the transport team is available at all times, with a back-up team available if necessary. The Winnipeg Ambulance Service transports the team on the ground if the emergency is within a 150 kilometre radius of Winnipeg; otherwise the team is flown by the Lifeflight-Manitoba Air Ambulance.

For more information, see our History of Neonatal Intensive Care.

Antenatal Home Care Program, 1985

The Antenatal Home Care Program was established in 1985. The program offered a community-based, safe alternative to hospital care for women experiencing complications of pregnancy including high blood pressure, preterm labour, premature preterm rupture of membranes (PPROM), or diabetes. A nurse would visit patients in their home to provide daily, semi-weekly, or weekly care, depending on the needs of the patient. This program was the first of its kind in Canada and the model from which many other Canadian programs were developed. It expanded its services in November 1991, and became part of the WRHA in 2000. Today it remains a thriving program at Women’s Hospital and offers personalized care at home, resulting in fewer patients in the hospital.

Nurse-led Clinics, 1990s

In the 1990s, women’s health care adapted to counteract the profound misunderstandings of necessary care. Where once women’s healthcare focused on reproductive organs, health concerns shifted to the totality of the female body. At HSC, nurse-led clinics, initiated by Wendy Spearman from Women’s Ambulatory Care, were developed and standardized. Nurse-led clinics were a revitalized service delivery model system created to maximize the knowledge and experience of an interdisciplinary team. The Clinics often operated out of the Outpatient Department. A nurse would be in charge of triaging patients to determine which care was needed and provide contiguous care throughout. Strongly encouraged by Myrna Rourke, then Director of the Women’s Hospital, Beth Brunsdon-Clark, Kathy Hamelin, Mary Dreidger, Teri Ibbott, and Donna Britton developed the method of care that would use all of the knowledge of nurses, pharmacists, and other specialists, enabling physicians to focus on medical care. They hoped to ensure that the service provided was based on the needs of the female patients. The first nurse-managed clinic was the Mature Women’s Program in 1993. They were also instrumental in Kangaroo Care, the Family Planning Program, and Family-Centred Mother-Baby Unit, to name a few.

Baby Friendly Initiative, 1991

The Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI), which launched in 1991 through UNICEF and WHO, was a global initiative to implement practices that protect, promote, and support breastfeeding. Breastfeeding had been replaced by formula feeding due to the acceptance and encouragement of formula use in hospitals. The BFHI encouraged hospitals to rectify this. A maternity facility would only be designated “baby friendly” once it implemented specific steps to support breastfeeding, including not accepting free or low-cost breast milk substitutes and feeding bottles.

The BFHI led to many nurse-driven practices in relation to maternal and baby’s health at the Women’s Hospital, including Kangaroo Care and Breastfeeding Service, and led to the overall family-centred mother and baby unit.

See the World Health Organization website for more information: https://www.who.int/nutrition/topics/bfhi/en/

Kangaroo Care, 1991

Kangaroo Care (also known as KC or skin-to-skin) was implemented in the Intermediate Care Nursery (Women’s Hospital) in 1991. The program encourages bonding through close physical contact between parents and their medically stable premature or sick baby.

Kathy Hamelin, Clinical Nurse Specialist, researched the principles of the program that had been practiced and studied in hospitals in Europe. The term “Kangaroo Care” was chosen because this method of caring for premature infants mirrors the intimate way kangaroos care for their young. The baby, wearing only a diaper, is held against the bare chest of a parent for as long as it is beneficial. Kangaroo Care was introduced to Canada at HSC, and has since been adopted across North America.

Physical contact has long-term physiological and psychological benefits for parent and baby. Parents contribute directly to the care of their baby: they gain confidence in caring for their premature infant, are less intimidated when they can take their baby home, and feel more connected with their babies emotionally. Before Kangaroo Care, mothers could not hold their babies until they were at least three pounds.

Most importantly, the program allows for the parent and child to get to know each other – it is believed the stimulation, warmth, and closeness that the baby receives from the physical contact with their parent promotes bonding, nurturing, and growth. It stabilizes them, keeps their heartrate up, and improves physical and neural development. Eye contact is enhanced and studies indicate babies may go home earlier than those who do not have the skin-to-skin contact.

Today this practice has expanded to all mother and baby relations. The Women’s Hospital has implemented a family-centred method of care, which includes more mother-and-baby bonding. At the new HSC Women’s Hospital, mothers and babies will be cared for as a unit, within the context of their families, and not separated unless absolutely necessary.

Mature Women’s Program, 1993

The Mature Women’s Program was created in 1993 as a joint initiative of the Women’s Hospital Ambulatory Care Department and Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Sciences. The program was the first nurse-managed clinic and interdisciplinary program at HSC. It provided women dealing with menopause and perimenopause direct access to a multidisciplinary expert team, including experts in medicine, nursing, pharmacy, nutrition, and social work. Teri Ibbott, Dr. Richard Boroditsky, Dr. Tom Brown, and Beth Brunsdon-Clark were instrumental in the development and implementation of the Mature Women’s Program.

The Program, though multidisciplinary, was led by a team of nurses. Unconventionally, the Program did not require referrals from doctors; rather, women could access the Mature Women’s Program directly through the Outpatient Department to get a nurse assessment. A nurse would determine whether and how treatment should proceed and connect the patient with appropriate healthcare providers, maintaining contiguous care as much as possible. The aging “Baby Boom” population and new emphasis on total women’s health made this program a necessity and the first of its kind in Winnipeg.

The Program could be divided into three phases. The Menopause Clinic was the first phase of the development of the Mature Women’s Program, which provided holistic health care for women who were having difficulty with menopause and related issues. The second phase emphasized H-Alt, or hysterectomy alternatives. Boroditsky challenged the traditional practice of hysterectomies (the complete removal of the uterus) and spent his life developing alternatives and changing perspectives on women’s health issues. The third phase, primarily developed outside of Women’s Hospital, was research into women’s health, including osteoporosis and cardiovascular disease.

The Program was run by an engaged clinical team who performed self-assessments on their understanding of women’s health before joining the Program. In an unprecedented move, the Program adapted its service base as it was being developed to the needs of the patients and the suggestions of the entire clinical team, rather than on the recommendations from the doctor alone.

In 2006, the Mature Women’s Program moved its operations to Victoria Hospital in the newly created Mature Women’s Centre under the direction of Boroditsky. It included clinics related to Menopause, Osteoporosis, Fracture Prevention, and Hysterectomy Alternatives. They also worked closely with CancerCare Manitoba to assist women of all ages who were experiencing menopausal concerns related to malignancy. The Centre also developed a Women’s Cardiac Health Program in association with the Lifestyle Program.

For over twenty years, the Mature Women’s Program addressed health-related, social, nutritional, and lifestyle issues in an attempt to better the well-being of patients. The care-giving team included a nurse clinician, gynecologist, family physician, clinical pharmacist, clinical dietician, and kinesiologist who consulted with specialists, including cardiologist, endocrinologist, urologist, psychologist, exercise specialist, and an alternative therapies consultant.

In 2017, the Mature Women’s Centre was closed due a reorganization of the Manitoba healthcare system. Some services were transferred to Women’s Hospital in 2018.

Midwifery Upgrade Challenge, 1997

In 1997, the Government of Manitoba assented to the Midwifery Act, wherein midwives could become primary health care providers. The Manitoba government issued a call for a formalized midwife education program to recognize and systematize alternative birthing methods. Beth Brunsdon-Clark, then Director of Women’s Health, helped to create the Midwifery Program to ensure women were getting the services they wanted.

The Midwife Program provided midwives with access to medicinal and practical training under the supervision of nurses and doctors. Through government funding, midwives had access to knowledge and patients to establish a professional service. Because of this, Women’s Hospital became a forerunner in alternative birthing methods. No other hospital in Canada provided training or services for this professional group.

Educational Director of the Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Science Margret Burrows, Judith Dietrich, Education Manager Brenda Stutsky, and Director Brunsdon-Clark worked to challenge the misconceptions of midwifery over a two-year period. They created a fair, reasonable, and achievable benchmark for midwife training, including a process of appeals through the Faculty of Nursing at the University of Manitoba. Midwives brought new perspectives regarding the birthing process to the Women’s Hospital and left with knowledge and understanding of the female body. Though challenging, the program paved the way for midwifery to be added to the Regional Community Health Portfolio in 2000. Midwife services continue to be made available for women at the current Women’s Hospital.

Breastfeeding Service, 1998

Under the direction of Beth Brunsdon-Clark, Clinical Nurse Specialist Kathy Hamelin developed and implemented the Breastfeeding Service in 1998.

In 1978, the World Health Organization and Health and Welfare Canada made breastfeeding a primary goal in the promotion of infant and child health. All levels of health care have endorsed it as the preferred method of infant feeding for at least the first four to six months of life. Hamelin felt that although breastfeeding was promoted, the professional support required to assist mothers who are experiencing difficulties with breastfeeding was not readily available. Hamelin’s drive to improve breastfeeding rates came as a result of research on premature infants. As part of that research, she became HSC’s first registered Lactation Consultant (an international certification) in 1994.

The demand for breastfeeding support was tremendous. Hamelin remembers women filling up the waiting room outside of her office for help. Approximately Nineteen percent of mothers at that time were under nineteen years old and a program was necessary to ensure the health of mother and baby. Due to this demand, a Breastfeeding Service opened in 1998 with the aid of private funding – starting with one full time and one part time staff. Through private funding they were able to hire the first Indigenous lactation consultant in Canada to support Indigenous mothers, who make up a large percentage of patients at Women’s Hospital. By 1999/2000, there were twenty-six lactation consultants at HSC, ensuring that all families at HSC had access to breastfeeding support and expertise.

Nurses provided breastfeeding support, encouragement, and advice to new mothers at Women’s Hospital, NICU, ICN, and Children’s Hospital (for babies that may have been re-admitted after being discharged from Women’s Hospital). The Breastfeeding Service at Women’s Hospital specializes in providing breastfeeding support to families in the hospital and community settings. The service provides consults to hospitals, receives referrals from pediatricians and community colleagues, and responds to phone inquiries. Though baby formula is available, breastfeeding is still largely encouraged at the Women’s Hospital.

As part of the program, the Breastfeeding Service also conducted a research program in order to determine the needs of families in the hospital and community. These findings direct future program development and ongoing research.

As of 2019, the Breastfeeding hotline is available 24 hours a day.

Women’s Family Birthplace/LDRP/Family-Centred Mother-Baby Unit, 2000

As women and their families became more educated about the birthing process, they began to seek alternatives for their birthing experience. By the 1990s, there was a clear need for a facility that could support a more family-centred approach to childbirth. Renovations were undertaken at Women’s Hospital to create the Women’s Family Birthplace (also known as LDRP, and Mother-Baby Unit), which had two main objectives: the safety of the mother and child, and the freedom for parents to choose the approach to the birth of their child.

Dr. James Allardice and Dr. Myrna Rourke were instrumental in the establishment of the Women’s Family Birthplace. Both envisioned a more home-like setting for healthy women to give birth to their babies.

The philosophy of the Women’s Family Birthplace lies in the experiences of the woman and her family, and the celebration of the birthing event. The new unit was modeled after the LDRP concept (Labour, Delivery, Recovery, Postpartum), offering a same-room, home-like environment where families could share in all phases of their low-risk birthing experience. The unit included seventeen specially equipped self-contained birthing rooms for low risk mothers-to-be. Each room featured such items as delivery beds, fetal monitors, infant warmers, respiratory equipment, and extra space for nursery care and nursing services. The birthing rooms and bathroom facilities offered much more space and comfort for the parents and family. Mothers (who were assessed as low-risk) would be assigned a birthing suite for the entire process of labour and one-on-one care provided by a nurse.

The unit focused on family-centred maternal and newborn care and allowed for multiple care providers from professions including obstetrics, registered nurses, midwives, family physicians, and allied health professionals to facilitate the birthing experience. The unit had its own LDRP staff, including registered nurses who were trained to provide optimal care during labour, and non-pharmacological approaches such as counter-pressure, hydrotherapy, and massage. After birth, newborns would room-in with their mothers – a practice that promoted and enhanced bonding.

If there were any complications during labour and delivery, patients could be easily transferred to the high-risk ward.

From a teaching perspective, the LDRP model of care – the cornerstone of the Women’s Family Birthplace – was invaluable as it provided students the opportunity to care for a family throughout the childbirth experience. The continuity of care that was encouraged, resulted in a trusting relationship developed between student and family. Staff would go out of their way to make a family comfortable, including allowing animals in the rooms and encouraging ethnic foods and customs. Beth Brunsdon-Clark, Director of Women’s Health, wanted to encourage ethnic ceremonies, such as Indigenous naming ceremonies, but space and resources limited the options available. The new HSC Women’s Hospital has dedicated spaces for spiritual ceremonies, making this dream a reality.

Due to a reconfiguration of the service model, Women’s Family Birthplace amalgamated with the high risk unit (LA2) in December 2016, in order to provide a better nurse/patient ratio and improve patient flow between units, closing the LDRP unit for good. The Prenatal Assessment Unit (PNAU) and triage area also amalgamated to form a nine-bed Triage unit. Although Labour, Delivery, and Recovery are still in one room, Postpartum care is delivered elsewhere in the hospital. The LDR model of care will be continued in the new HSC Women’s Hospital.

Neonatal Family Support Program/ Veteran Parent Program, 2005

The Neonatal Family Support program began in October 2005. The program was developed by the Neonatal Developmental and Family-Centred Care Committee with the support of the Winnipeg Foundation. The program was developed to provide peer support and connect parents whose babies are in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) with volunteers who have gone through the same experience, can relate to what they are experiencing, and help them with whatever they need.

When the program began, the volunteer parents attended a workshop that provided them with training in helping parents cope. The training included teaching parent volunteers how to talk to people, listening skills, and how to be respectful of different methods of care. Support was primarily provided over the phone, in person, or through email.

The program operated in all of Manitoba’s NICUs: HSC Children’s Hospital, St. Boniface General Hospital, and Brandon Regional Health Care Centre. In 2008, the Program ended due to lack of funding. In 2018, the program was resurrected and renamed the Veteran Parent Program. It is offered at HSC and St. Boniface Hospital.

For more information, see our History of Neonatal Intensive Care and the Children’s Hospital Foundation website.

Prenatal Connections Program, 2011

The Prenatal Connection Program began in 2011 in partnership with Manitoba Health and under the direction of the Winnipeg Regional Health Authority. This nurse-managed clinic provides one-on-one prenatal assistance for high-risk mothers. The Program combines research and action to develop and improve upon services for women who have to leave their homes and families to give birth and/or obtain specialized obstetrical care in Winnipeg. In 2011, researchers worked with women staying at Kivilliq Boarding Home, Norway House Boarding Home, Ekota Lodge, and Swampy Cree Receiving Home to gain their perspective on improving HSC’s service delivery model. A Needs Assessment was completed in 2014 and evaluated in 2016. The evaluation results will be used during strategic planning sessions to expand and improve the program in future. Wendy Spearman was vital to the development of this program.

Partners in Inner-City Integrated Prenatal Care Project, 2012

The Partners in Inner-city Integrated Prenatal Care Project (PIIPC) started in 2012 and was led by a research team comprised of physicians, registered nurses, and government stakeholders to reduce barriers to prenatal care for pregnant women in inner-city Winnipeg. Barriers included not understanding the need for prenatal care, not knowing where to access care, mistrust of care/fear of being judged, and the lack of transportation or childcare in order to attend prenatal appointments.

Some of the improvements made by the PIIPC Project included:

- Adding midwifery care to selected Healthy Baby/Healthy Start community groups.

- Making prenatal care more convenient, flexible, and welcoming. Supports such as bus tickets, food, and a “pregnancy passport” helped moms participate.

- Enhancing outreach to pregnant women through the Street Connections van.

- Launching “This Way to a Healthy Baby” marketing campaign using multiple strategies – see website http://www.thiswaytoahealthybaby.com/ (University of Manitoba/WRHA partnership).

The program has been very successful, with improved outcomes for mothers and babies. PIIPC clients benefited from earlier access to prenatal care, increased prenatal visits, and more fetal assessment unit visits. Integrated care is also provided by linking women with other relevant services such as social work, Child and Family Services, and addiction services. Collaboration among professionals and programs also improved through use of this family-centred model.

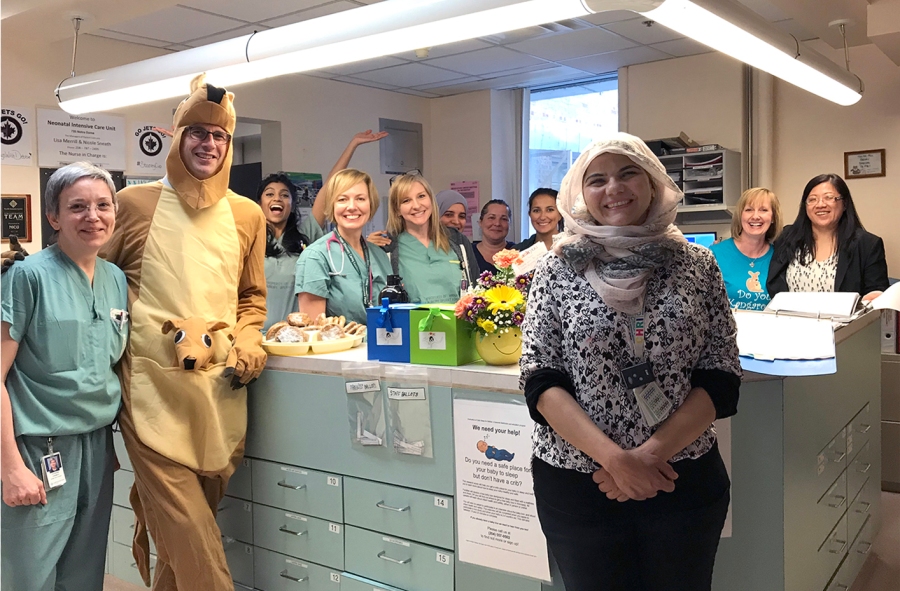

Mothers/Methadone Program, 2015

The Mothers/Methadone Program is a nurse-led collaborative pilot project that began at Women’s Hospital in 2015. The project found that family-centred care was beneficial for newborn babies of opiate-addicted mothers who are on methadone maintenance treatment.

Clinical Nurse Specialist, Lisa Merrill, led the project, which was based on a similar method of care in a Women’s Hospital in British Columbia. The project involved collaboration with the Immediate Care Nursery and Family-Centred Mother & Baby Unit (FCMBU). In this program, mothers and babies were kept together, they encouraged the use of skin-to-skin bonding methods, and mothers had greater access to assistance and support with breastfeeding. This family-centred care had immediate results in helping with withdrawal symptoms, facilitating the bond between mothers and babies, and the overall health of babies who were affected by opiate abuse in utero. The pilot project also reduced stress for mothers who previously had to travel back and forth to visit their babies in the hospital. Mary Driedger, who works alongside social workers from Child and Family Services, was also instrumental in the project.

Women and maternal health at HSC Winnipeg has benefited from the care, ingenuity, and engineering of doctors, nurses, and staff for over 130 years. Though this list of research and programs is not exhaustive, it gives you an understanding of the care provided in the past, and the foundation of care upon which the new HSC Women’s Hospital will build in the future. The HSC Women’s Hospital is the largest and most complex health care project in Manitoba’s history, with regard to its size and technology, as well as the programs it will implement. Every effort is being made to create a comfortable, inclusive, and caring environment that will benefit the patient, family, and staff. With the opening of HSC Women’s Hospital, women’s and maternal care will continue to grow and thrive.