After 130 years of existence, certain stories stand as examples of perseverance, excellence, and transition. Here is a more intimate look at the history of women’s and maternal health from an institutional perspective.

Baby Boom and the Creation of the Maternity Pavilion

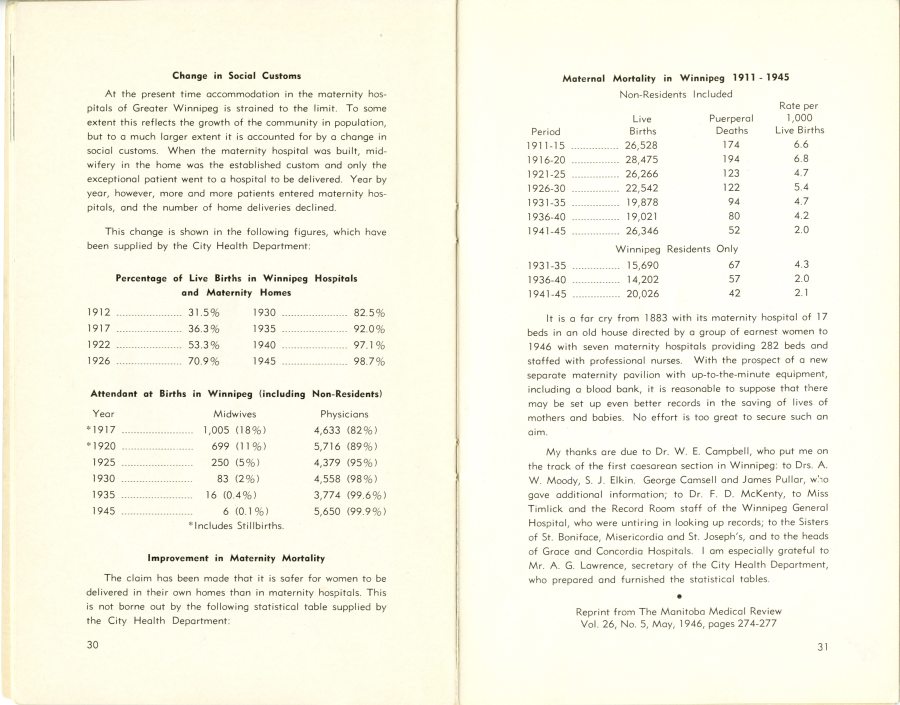

With the end of World War Two and subsequent “Baby Boom”, obstetrics facilities at Winnipeg General Hospital were stressed due to a shortage of beds and overcrowding on the wards and in the nurseries. In the 1944 Annual Report, Dr. Frederick McGuinness, Head, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, reported 1,400 births, including thirteen sets of twins. He cited an “urgent need” for a separate obstetrical and maternity hospital – the current 50-bed Maternity Ward was bursting at the seams! An isolation area was not available for mothers and newborns, and the labour/delivery room was inadequate to handle the volume of births. Despite these challenges, the department had excellent outcomes in the areas of maternal mortality, infant mortality, and morbidity.

Pressure from Dr. McGuinness, serious overcrowding, and wait lists, led the Winnipeg General Hospital Board of Directors to review the construction program and in 1945 there was unanimous agreement that a Maternity Pavilion should be constructed separate from the main hospital. The City of Winnipeg agreed to provide a $900,000 bond for the Maternity Pavilion, and in 1946 the excavation of the site located at Notre Dame (between Emily and Pearl Streets) was undertaken. By 1947 the architect’s drawings were complete and a call for tenders was issued.

Although significant financial pressures delayed construction by a year, in 1948 the Board agreed the Maternity Pavilion had to be built despite the high costs. Bird Construction Company Limited was awarded the contract and work began in June 1948. By the end of the year, the steel and concrete structure was completed and four of the five storeys were bricked in. Steam was supplied by the Power House so interior work could be done during the winter months.

The Flood!

After the official opening of the Maternity Pavilion – 26 April 1950 – the plan was to transition patients and staff to the new facility over a two week period. At this same time, the 1950 Red River Flood was wreaking havoc on other hospitals in the city, forcing them to evacuate patients. Winnipeg General Hospital was called upon to find as many beds as possible for patients from St. Boniface, while already accommodating evacuees from rural hospitals (733 in total). Hospital officials became concerned that the newly constructed – and very available – Maternity Pavilion might be pressed into service as an emergency shelter, leading to fears that infections might be introduced into the new building.

On Saturday 6 May 1950, Dr. Harry Coppinger, Superintendent, Winnipeg General Hospital, advised Dr. McGuinness (Head, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology) to assemble members of his staff, and anyone else who could help, to move patients from the maternity wards (West 4 and West 5) to the Maternity Pavilion in order to accommodate incoming patients from St. Boniface Hospital.

Grace Johnson recollects, “It seemed almost impossible at first, but every available person from the probationers right up the line worked steadily and cooperatively. Beds were made, wards cleaned

and dusted, equipment scrubbed and sterilized, the whole place hummed with activity. Patients began to be moved by 1:45 pm and the last baby was brought over by 3:30pm that same day.”

The first birth in the Pavilion took place on the day it opened – Mrs. Betty Goosen of Rosenort gave birth to a daughter. Two more babies were born before 6:00 pm that day. Between 6 May and 31 December 1950, 1,846 babies were delivered at the Maternity Pavilion.

The Trials of Betty Goosen, excerpts from Julie Vandervoort’s Tell the Driver[1]

In the spring of 1950, residents of Red River Valley were under serious threat from rising flood waters. As a result, between 20 April and 6 May the town of Morris was evacuated. At nine months pregnant, and living several miles from the nearest hospital in Morris, Betty Goosen (also known as Goossen or Gossin in other accounts), along with her husband Walter, were in dire straits.

“Mrs. Goosen had gone to the Morris Hospital on April 28, making the trip partially by boat. There, she hoped to wait out the remaining few days until her baby was born. But the flood workers couldn’t save the Morris Hospital. When one of the last trains able to get through left Morris for Winnipeg on May 4, she was on it, expecting her labour pains to start any minute. . . . [W]hen Mrs. Goosen arrived at the Winnipeg General, her labour finally under way[,] she’d already been through a lot. It was probably just as well she didn’t know the entire Maternity Department was about to suddenly change location. . . . There was a sense, from those who remembered the move, that hospital officials didn’t want soldiers and refugees in the new Pavilion because of the ever-present fear of infection; the only way to keep them out was for the hospital to occupy the Pavilion itself. . . . Mrs. Goosen remembers that ride. Her baby was about to be born and her labour pains were severe. She didn’t know where her husband and two small children were or what had happened to their home and livestock. Telephone use was restricted to emergencies, so her husband didn’t know how she was either. In the last days of pregnancy, heavy and awkward, she had had to climb in and out of boats to get to the train. Now she was being rushed through a long tunnel, about to be delivered by a doctor she didn’t know. Although this was her third baby, she was afraid. The nurse seemed upset with her for not answering questions, and the orderly wanted to know if she was excited about her baby being the first one born in the new Pavilion! But it all ended well. Mrs. Goosen had a healthy baby daughter, born, according to Elinor [Black]’s history, “in one of the delivery rooms, all proper and correct”. Proper, correct, and two minutes after reaching the delivery room. Flood damage was such that it was a month before Mrs. Goosen could return to her home in Rosenort, but she got out of the hospital in four days by promising to take it easy and stay with relatives.”

[1] Julie Vandervoort, Tell the Driver: A Biography of Elinor F.E. Black, M.D. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 1992, pg. 176-180.

Indigenous Health and NICU, excerpt from Healing & Hope[2]

Margaret Lavallee, Director of Native Services in 1978, helped the department go from primarily translation services to one of advocacy. “This is a different culture, a different way of living”, she explains. “Patients bring their culture with them. It was sometimes very scary for people to be in this place where nobody spoke their language or even ate the same food. Our goal was to build bridges between the two cultures and then on top of that to translate all of the medical terminology.”

She recalls once incident that involved a family of a young baby. The parents wanted a sacred pipe and eagle feather placed near the head of the infant in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit for one hour at sunrise and one hour at sundown over the course of four days. The nursing team leader agreed to the arrangement and understood that staff members could not touch the pipe. But there was another part of the tradition that was potentially more complicated: no menstruating woman was allowed to come near the pipe. Knowing that this was too personal an issue to raise with the nurses in the unit, Lavallee followed a tradition of putting tobacco down outside and asked for direction from higher powers. The solution came to her in a dream. She contacted an Aboriginal leader who arranged to hire a male nursing student for one hour each morning and evening.

[2] Health Sciences Centre, Winnipeg, Healing & Hope: A History of Health Sciences Centre Winnipeg. Winnipeg: Health Sciences Centre, 2009, pg. 148.

60th Anniversary of Women’s Hospital, 2010

6 May 2010 was the 60th anniversary of the Women’s Hospital. Within its 60 year history more than 225,000 babies were born there. To celebrate, Health Sciences Centre launched a year of celebration of the work at Women’s Hospital, starting with cake!

Pat Gregory, Program Director and Director of Patient Services for Women’s Hospital, helped organize the event and served as emcee for the kickoff anniversary celebrations. Special guest speakers included Dr. Maggie Morris, Kathy Hamelin, and Mary Driedger. All three spoke of the history of the hospital and changes in philosophy, research, education, and practice during their tenure. They were joined by Sylvie Boudreau who brought greetings as Aboriginal Liaison. The speeches were concluded by Health Minister Theresa Oswald with the reading of a proclamation from the Provincial Government that declared 2-8 May 2010 as “Women’s Hospital Week”.

Special pins were created and distributed for the event. After much debate about what symbol could represent women’s and maternal health care, designer Cam Walker and planning committee members Donna Henry and Lorie Mayer, proposed a rose and rosebud theme. Though unknown at the time, this symbol harkens back to the early days of the Maternity Pavilion, when roses were sold by the White Cross Guild to raise money for the newly opened facility. The rose and rosebud theme, which incorporated the HSC corporate colour palette, was also used in advertisements for the anniversary birthday party.

On 23 September 2010, HSC staff who were born at or had children at the Women’s Hospital were gathered for a “family” photo to celebrate the anniversary. Staff gathered to commemorate the hospital that united them as a family, professionally and personally.

The year ended with the installation of a display of archives and artifacts curated by the HSC Archives/Museum. The components of the display were sourced primarily from the Nurses Alumni Association of the Winnipeg General Hospital/Health Sciences Centre, with additional information supplied by Judy Babb, Jordan Bass (Faculty of Medicine Archives), and HSC Communications. Under the direction of Emma Prescott, Archivist, the display was assembled by retired nurses Pat Powell and Dolly Gembey. It showcased some of the research, initiatives, and practices developed at Women’s Hospital that set the standard for women’s health care across Canada.

A Rose is a Rose is a Rose

Over the years, roses – and flowers in general – have become a symbol of women’s health at HSC. In three separate events, and without reference to each other, flowers were chosen to commemorate the Women’s Hospital.

In 1950, the White Cross Guild sold roses over the course of a year to celebrate the opening of the Maternity Pavilion. In 1951, the proceeds of those sales were used to buy one hundred copper vases for patient rooms in the Pavilion.

Nearly sixty years later, and with the anniversary of the Women’s Hospital quickly approaching, the planning committee needed a symbol to represent women’s health. That symbol was to appear on a commemorative pin and on anniversary bulletins. Though many suggestions were given – including a bottle or a rattle – ultimately a rose and rosebud won the day. The committee concluded that the flower and bud appropriately symbolized health care for women at all stages of life.

In 2007, when HSC announced plans to construct a new Women’s Hospital, it called for the community to help pick the design scheme. Between blankets and wildflowers, those who participated overwhelmingly voted for the wildflower theme. Though not roses specifically, it was clear that the floral imagery sparked the same connections in the community as the rose and rosebud did for the 60th anniversary planning committee.

What’s in a Name?

The Women’s Hospital at HSC has gone through a series of name changes over the years. Historically, the facility that housed women’s health was known as the Maternity Hospital and then Maternity Wards in the Winnipeg General Hospital. With the opening of a new facility, the initial name – Maternity Pavilion, used from 1950 to 1957 – was a continuation of nomenclature used for its immediate predecessor, the maternity wards. Though many people continue to call it the Pavilion, it has not been the Pavilion since the early 1970s. It quickly became evident that health care was being provided to more than just maternity patients, and the second name – Women’s Pavilion – was born in 1957. The facility remained Women’s Pavilion until 1973 when the third name – Women’s Centre – was adopted. 1973 was the same year that the Health Sciences Centre was established. In 1979, the facility came to be known as the HSC Women’s Hospital – the most enduring of the names. The new hospital will maintain this title. The numerous name changes give insight into the evolving nature of women’s health and the history of the hospital.